Metafiction and Beyond: 'Galilee' by Clive Barker

Introduction

Oh, a big house full of magic, like the one in Barker’s earlier book The Thief of Always? No, not quite. The house and the story here are bigger, and no, don’t give this book to your children. So where do I begin my review? How do I narrate it? Hmm… I guess this is something writers often struggle with, even Barker. In Galilee, through his metafictional experiment using Maddox, a demigod writer living in the house, Barker shares his writing process, which is the best part of the story.

Barker = Maddox;

This letter was republished in Medium’s Books Are Our Superpower, a publication for book reviews, recommendations, summaries, rants… Feel free to read and clap there!

Literature review

First, let me share some knowledge so you understand my perspective. I read Weaveworld around 20 years ago in Hungarian and it mesmerized me. I couldn’t put it down. It was a book that I picked up from a shelf without even reading the blurb. (I don’t like trailers; they spoil too much.) After that, I read the Abarat series and loved it too. I even bought the hardcover versions recently, complete with all of Barker’s brilliant paintings. A few years later, I read the first two in the Books of the Art series in English, but since my English wasn’t really good, I couldn’t fully immerse myself in the world. However, I still enjoyed them and should probably reread them once the third book in this series is published. Oh, and this year I watched some of Barker’s films (Hellraiser, Midnight Meat Train, and Nightbreed) but didn’t like them much. I do really enjoy watching his A-Z of Horror series; they are educational! I also watched some interviews with him online, and he is very charming. I remember someone describing the young Barker as beautiful, the middle-aged one as buff, and what we have now… I can’t remember. Unfortunately, his illness took away a few of those previous characteristics. It makes me sad to see him in a wheelchair. Anyway, let’s go back to the books.

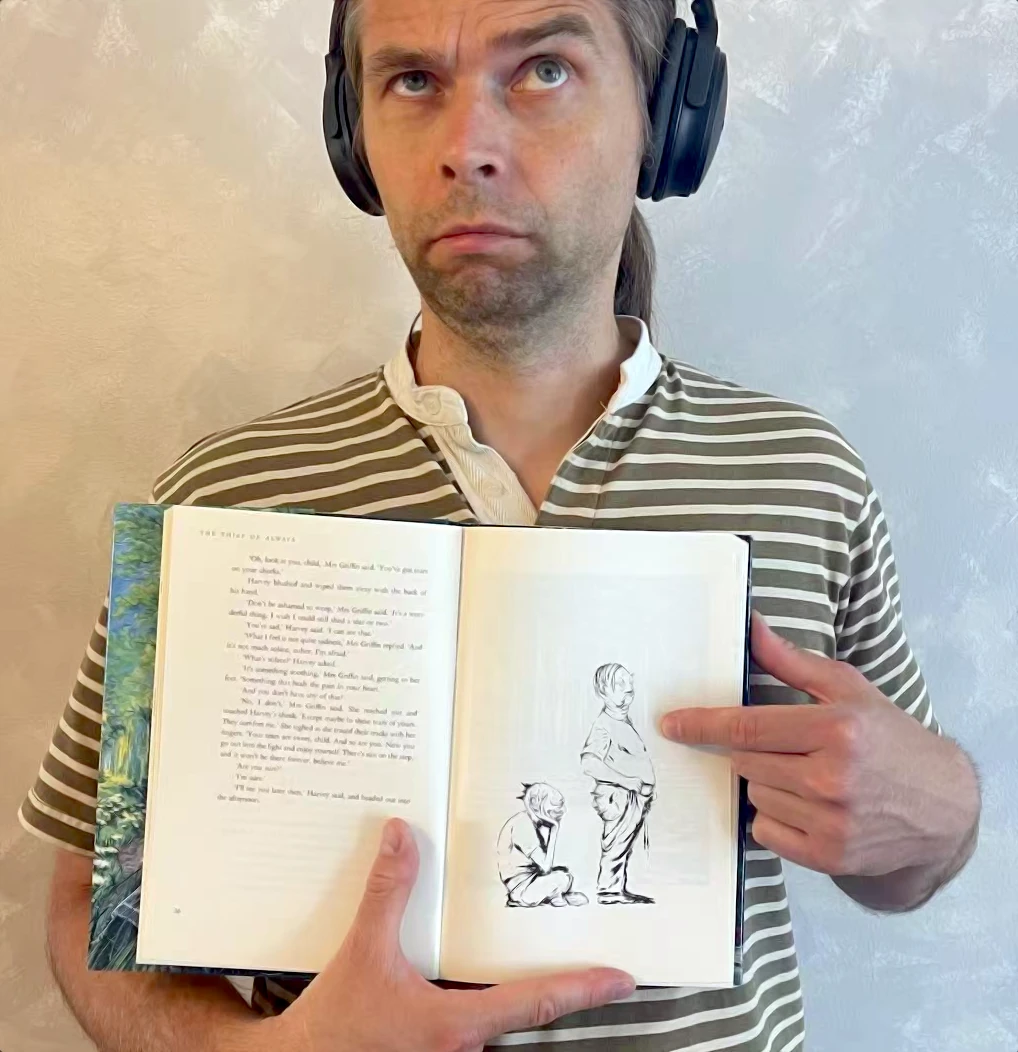

Last year, I thought my English was good enough to read more of his works, so I (re)started with The Thief of Always. I loved it but am still puzzled by the drawing where a man looks at another’s backside. I don’t know how that drawing got in there. All the other drawings in this book are linked to the story; this one doesn’t seem to be. Any ideas?

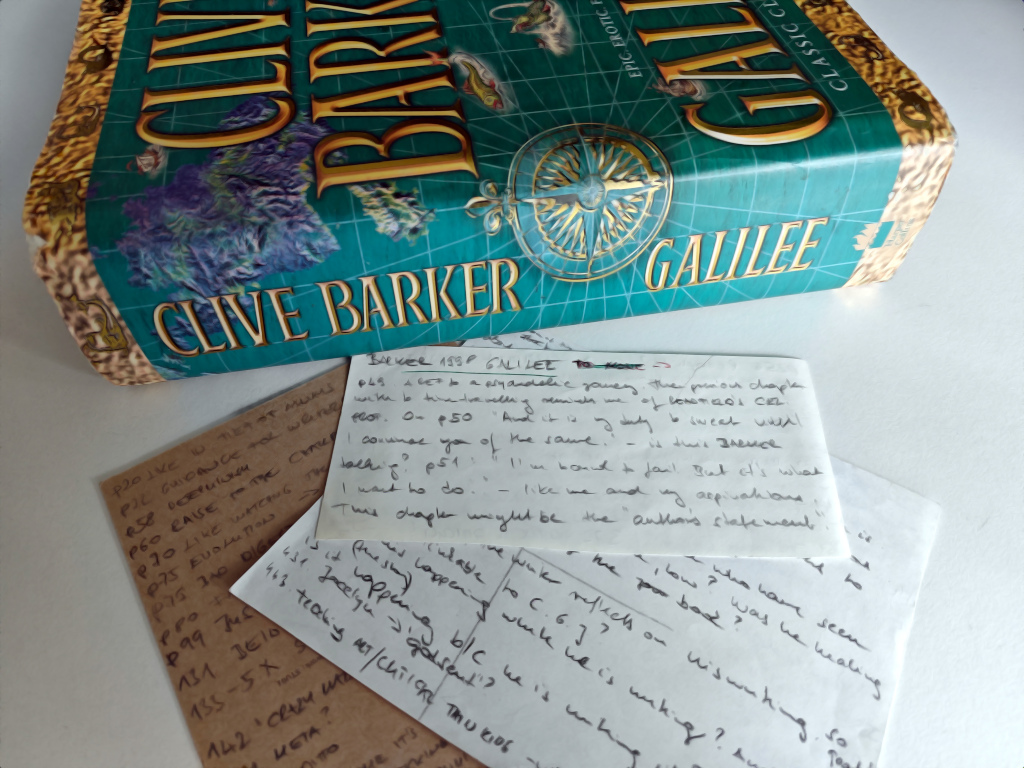

I read somewhere that Galilee isn’t a typical Barker book, so I thought let’s try it because I like when artists experiment and don’t stick to their established methods. I enjoy seeing them try new things to discover more about themselves because this is something I do to in my practice. And I guess this is what I found in Galilee, an experiment. After finishing this hefty book, I also read the relevant page on Barker’s site (clivebarker.info), the corresponding chapter in The Dark Fantastic (Winter 2002), and reviews on the Goodreads website. Let’s start with a quick summary of these reviews.

Goodreads reviews

Many 1- and 2-star reviewers gave up on finishing the book because they found it boring or too long, with unnecessary characters and too much focus on rich snobs. They disliked the narrator (Maddox) and expected more horror/paranormal elements. Some thought the ending didn’t climax enough, while others found parts too weird, for example the two brothers talking about their dad’s massive penis or Rachel worshipping Galilee’s. I wasn’t too keen on some of the sex nor Rachel’s worship either, possibly because I am a heterosexual male, but these parts didn’t bother me much. However, the pedophilic elements did; one where a daughter might be allowed to play with her father’s penis when she gets older and another involving a young girl having sex with a water spirit. I still don’t understand this latter story. Okay, Galilee is the water spirit I guess, but then who is Jerushka? Rachel? I’ll have to read Gabriella Kristjanson’s work on the predatory realms in Barker’s works to understand more about this theme. Looking at her publication list, she seems to be the expert.

The 3-star reviews are more realistic; they point out both the good and the bad. They liked that Barker writes through Maddox and that the book is well-written but often didn’t like Rachel’s relationship with Galilee. They wrote, “it felt forced,” and also that the characters weren’t really interesting either. Someone noted: “There was also an excessive preoccupation with sex and licentiousness, which was needlessly thrown into the narrative as a shock tactic and didn’t connect with the greater story or convey any deeper purpose.” I’m still on the fence about this. As mentioned above, apart from the pedophilic images, the rest didn’t bother me. Well, maybe the necrophilia a bit too. By the way, how Garrison’s character evolves is very interesting: how he gradually allows himself to become someone he really wants to be.

The 4- and 5-star reviewers are those I agree with most. They often wrote that you understand more upon rereading the book and that it’s a challenging novel. Some appreciated Barker’s research into both magical and historical aspects, e.g., the Civil War. Some agreed that Rachel and Galilee were the least interesting characters, resonating with previously mentioned 2-star reviews and my own feelings. Someone wrote that Rachel was irritating. Also, some still say the book is too long, and I somewhat agree but would need to reread it to be sure. There’s so much in this novel; maybe it’s not meant to be read once only?! By the way, I like the family trees at the start of the book. They help, but unfortunately can also spoil some developments because they foreshadow when someone dies.

The most liked review says: “Clive Barker writes fantasy like a person who lives in that world (because I believe he does).” Yes, I felt that too, especially after watching the video interview linked to his paintings for Abarat. He is able to immerse himself in his worlds while creating them. You can find this video on YouTube; it’s called The Artist’s Passion. See embedded below.

Personal reflections and questions

“You must write fearlessly!” (p.20) Maddox tells himself at the start of the book, which is likely something Barker is telling himself when he writes as well, for example when he’s unsure what to do with the characters or the narrative. As mentioned earlier, the metafiction - Barker talking to us through Maddox - is my favorite part of the book: the record of a storyteller’s struggle with his work and how he keeps himself motivated, for instance, by asking the question “Why do we write?” One of his answers in the book is that “We write to educate people, to pass on knowledge.” And it’s not just Maddox that Barker uses to encourage writers to write; it’s through Zelim as well, who is another storyteller in the book. Zelim educates people to make sure they don’t hurt or get hurt like he did.

And let’s talk a bit about the romantic element between Rachel and Galilee, inspired by Barker’s relationship with David Armstrong (Winter, 2001). For me, this is one of the least interesting parts of the story. But this book is worth rereading, and when I do, I might believe in Rachel’s love for Galilee. Currently, their love isn’t convincing to me; it doesn’t feel real… But wait! Now that I am thinking about it, I remember falling in love quickly and deeply a few times in my life and I did feel happily lost and probably a bit crazy too. So maybe Rachel’s love is more understandable for readers who are in love when reading the book. Somewhere Barker said that he was in love while writing. So there you have it. Read it when you are in love, and you might love the book even more!

I look at my notes and see a few other things:

There seems to be a discussion about determinism, particularly the notion of being “enslaved by gods,” which touches on an existential theme I think central to the story. How much free will did the characters truly possess? At times, I even questioned whether all of it is happening simply because Maddox wrote it down. Look, on p. 429, we read:

I suspect, by the way, that in the creation of divinities we see the most revealing work of the human imagination. And of course, in the life of that imagination, the most compelling evidence of the divine in man. Each of these other’s most illuminating labor.

Are we co-creating the story while reading? Okay, let’s not go down this rabbit hole today.

We also learn about Barker’s perspectives on societal norms, marriage, and power dynamics, and I wonder how these relate to this quote from the book:

[In a country] where the rich were kind and the poor had God.

The Gearys weren’t very kind. Neither were the Barbarossas. So, what is this country? Did the rich give God to the poor so they would stay quiet?

Other questions I still have:

- I remember two horses: the resurrected dark one and Holt’s. Was the latter white? If so, would that be a Taoist symbol?

- Why did Maddox lose his wife on the same night Galilee came back with Holt and Nub?

- Not sure why, but after a while, Rachel felt like Anne Hathaway, and Maddox as Tenzin in The Legend of Korra. I saw her face and heard his voice. Why?

- On page 443, when Cesaria says that the painting on the Gearys’ wall is “very male”, that “it’s trying too hard”, and she (a female archetype?) likes this, is she longing for Nicodemus? Very likely.

So yes, I should reread this book.

One thing that annoyed me at the end was the big reveal about why all this is happening - that is, why does Galilee sleep with the Geary women? If you read the book, you know why. But can you believe it? Are all super-rich people so occupied with money and power that they can’t satisfy their wives sexually or romantically? Or did only Nub think this would help because he couldn’t do it himself and then created a backup plan for his offspring in case they don’t fall far from the tree? And what about poor or middle-class people who might not be able to hire gods of lust? Should we hire less expensive prostitutes to make our partners happy if we can’t? Or should we try talking, communicating, and evolving together? I guess that’s what Galilee and Rachel are doing now, right? Talking.

Finally, allow me to finish with one of my favorite parts from Maddox (p. 536):

Nobody knows the whole story, of course, nobody can. Perhaps there is no thing entire; only that rubble that Heraclitus celebrates. At the beginning of this book I boasted that I’d tell everything, and I failed. Now Galilee promises to do the same thing, and he’s fated to fail the same way. But I’ve come to see that as nothing can be made that isn’t flawed, the challenge is twofold: first, not to berate oneself for what is, after all, inevitable; and second, to see in our failed perfection a different thing; a truer thing, perhaps, because it contains both our ambitions and the spoiling of that ambition; the exhaustion of order, and the discovery – in the mids of despair – that the beast doffing the heels of beauty has a beauty all of its own.

Reference

- Winter, Douglas 2002, Clive Barker, The Dark Fantastic. (The Authorized Biography), Harper Collins